A while ago, I found my book about Behavioral Economics - it’s a great book called Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman. Behavioral Economics, like regular Economics, tries to understand how people make choices. In the world we constantly observe that people move away from the optimal decisions dictated by economic models and choose sub-optimal alternatives, so the “Behavioral” part adds a new dimension and tries to explain: Why is this? Why would a person go against their own interests?

Well, the answer is simple, our minds are not truth-seeking machines, as many might assume. They are programmed for direct and indirect survival (except for some specific exceptions), which sometimes is at odds with truth, especially truths on a macro scale, where our intuition starts failing. And this reality manifests in a number of very interesting cognitive phenomena. Our ability to make the economically optimal decision is bounded by:

The amount of information available to us

Our ability to rationally process said information

The time available for us to make decisions

Human emotion and bias

My expertise in this field is not extensive at all, I pretty much know as much as the average guy who is casually into this topic; nonetheless, i find it really interesting. I had a professor of Advanced Microeconomics called Andrei Gomberg, who was actually born in the Soviet Union and has all kinds of interesting KGB stories and whatnot. He taught us some things about behavioral economics, why he thought human beings were natural conspiracy theorists and why the conclusions drawn from Behavioral Economics models are not always mathematically translatable to Macroeconomic Theory (a good exception: the Neo-Keynesian Phillips curve and inflation expectations, which is a behavioral trait but doesn’t directly come from the discipline of Behavioral Economics).

Why it Matters

Behavioral Economics matters because it’s a way in which economic agents can use data to help them increase sales, satisfaction, marketing efficiency, etc. Most things you encounter in your everyday life have been somewhat adjusted to account for cognitive biases and intentional sub-optimal choice, from you Netflix or Instagram algorithm to your retirement savings plan. Understanding these better is interesting and potentially beneficial for most agents as a defensive or offensive strategy to improve a particular result in all ways of life.

Now, let’s dive deeper into the Paradox.

Choice Paradox

One of the very interesting findings of Behavioral Economics is The Paradox of Choice. The term was originally popularized by psychologist Barry Schwartz in his book The Paradox of Choice – Why More Is Less. The overall idea, as I understand it right now, is as follows:

More optionality, intuitively, is supposed to help us be more satisfied with the decisions, this because the odds of finding a choice that better fits our overall wants or needs is more likely to exists the more options there are, Schwartz’s study contradicts this, saying that not only is it harder to choose with an over-abundance of options, but the overall satisfaction that people get from their actual choice is diminished. Now, I HAVE NOT READ THE BOOK NOR HAVE I DONE DEEP RESEARCH INTO THIS TOPIC, I did not even thoroughly check if the concept is 100% correct… why? because you people don’t deserve that, you don’t deserve a government and you don’t deserve your Amazon Prime accounts, because of your behavior.

Just kidding, haha, you know ILY. I did this because I think it might be interesting to do research by writing. This also means the article will be longer, as I will have to lay out the whole process… so for those who stick around, I will have a prize for you at the end.

The Paradox’s Paradox (Before)

How I’m thinking about this concept as of Nov 10th, 2024, is that some amount of choice is beneficial to overall satisfaction, but too many choices lead to a decline in satisfaction.

Look at the graph below. Again, this is how I intuitively understand the concept right now. This is not actual data. It’s just the concept I have in my head, based on average conventional knowledge. Initially, because there is only one choice, people will likely react to this choice in a very varied way. Some will feel extreme satisfaction and others extreme dissatisfaction, as you get some moderate amount of choices it is likely that less people feel extreme dissatisfaction, because they found a better alternative, but the extreme satisfaction some people felt (or the amount of satisfaction) is also dampened by the introduction of opportunity cost: if there are two or more ways to satisfy this want/need, I can start thinking of ways it could be satisfied in a better way, mentally increasing the opportunity cost of choosing. And the effect goes on and on with more choice, potentially even ending up with less average satisfaction than if there were only one single option.

The blue dots are individual “satisfaction points,” and the line is the average. Now, on this graph, of course, there would be outliers, where some individual might experience more satisfaction with 2 options than any people will with one, but this are left out for practical purposes.

Now, the second derivative of the paradox is: if the choice paradox is true, why are the so many different options in the market for most products and services?, why would companies go through all the trouble of having 100+ different product lines to satisfy the same general need/want, if the satisfaction people get can trend lower. As an example look at the cell phone ranges for Samsung, there is a huge amount of different smartphones, it would be impossible for a person to keep up with this.

Well, my guess, or hypothesis, would be:

If a person anticipates extreme dissatisfaction with making a choice when having very few options, they can just opt out of making the choice. When increasing the amount of choice, their happy customers are a bit less happy, but their sad customers are less sad. Human beings tend to have a Negativity Bias where negative experiences have greater emotional (psychological) impact on us than positive or neutral experiences. So, two things follow from this:

It is easier to get twice as much people buy the same product than to charge double the price to half of the customers. The elasticity of more optionality favors (the derivative on satisfaction vs optionality) is some sort of an L shaped function.

By increasing choice, the psychological impact on your customers is net positive given the negativity bias. After the increase in optionality, your happy customers will become less sad in proportion to how more happy your sad customers become. Something analogous to pricing power but for increasing options, perhaps optionality power, to a point.

Now, this is my hypothesis, in order to prove true/false we can go to the data of the studies and understand how the actual data is gathered, if the concepts are correct, if the results are reproducible, etc.

So, let’s start:

The Actual Choice Paradox

So, I came back on Nov 11 2024 (a day after) after having done a bit of research from the man himself and I came to the conclusion that my idea of the Choice Paradox could be refined but it was pretty close to the real concept coined by Schwartz, so, basically, the thesis is some choice is great but too much choice might be worse than non at all. Why? Well modern affluent western societies go through this scheme to determine that more choice is better:

+ Wellbeing = Better // + Freedom = + Wellbeing // + Choice = + Freedom => + Choice = + Wellbeing

The Choice Paradox tries to push back against this with four main arguments:

Choice Paralysis (paralysis by analysis): when people are faced with too many alternatives they feel like they have to explore all of them in depth so they can find the best alternative, because they are so many, no one can actually reasonably go through all of them. People become preoccupied with making the wrong choice and sometimes end up not making a choice at all. Schwartz gives an example about mutual funds for savings, where adding 10 extra options on funds decreased overall participation by 2%

Accumulation of perceived opportunity cost = less choice satisfaction: when people actually commit to a choice they get to experience their choice. According to the paradox, if there were too many alternatives to choose from the perceived opportunity cost from actually choosing becomes greater. The more options there are the easier it is to imagine something better out there that I could have purchased and I didn’t making my choice less satisfactory a-posteriori (after the fact).

Escalation of expectations: if there is a lot of optionality, my expectations for the quality of what I will be able to find grow, meaning that, in each decision I make, my expectations are going to be higher with more options, leading to more disappointment or at least a decrease in being pleasantly surprised.

Self-Blame: when there is only 1 choice and im dissatisfied by it, I intuitively understand that…

But if there are lots of alternatives, I absorb the responsibility of having chosen wrong. Making me feel worse

So, in general, according to this thesis: when there are lots of options I find it much harder to chose = a worse purchase experience, I am less satisfied with whatever choice I make = worse consumption experience and I feel personally guilty for being dissatisfied. So, in general, the relationship between optionality vs. satisfaction is actually somewhat parabolic as I showed in the above graph, but, according to Schwartz, can actually have satisfaction AND ease of choice (actually choosing) on the Y-Axis:

Where Does it Come From?

At first glance, I think most people have felt overwhelmed by choices in this modern world, meaning: What phone should I buy? Who should I date? Where should I travel? What should I major in?, etc. but we need to see the other side of thee room to understand if this is a statistically significant phenomenon that is repeatedly appearing through human experience.

There is a very famous experiment called the “jam experiment”, that is often cited as direct evidence for the choice paradox. It consisted on 3 separate studies

The Jam study: there was a stand placed in a supermarket offering samples of Jam, in one scenario there were 24 options, in the other scenario only 6. Tasters were offered discount coupons to purchase the jam. Initially, 60% of by-passers were attracted by the booth with 24 options, as opposed to only 40% to the one with 6%. So the stand with more choice was more attention grabbing. On the other hand, 3% of tasters of the 24 option stand purchased the jam, compared to 30% from the 6 option stand. This seems huge, it’s a 10X difference on sales

When examining the paper in depth, the environment seems to be controlled for variables like time of the year, place, prices, etc. So the claim is that: people who had more choice did not chose.

Essay Study: Students were given an essay assignment, in one scenario there where 6 potential topics and on the other 30 potential topics. The completion % of the scenario with 6 topics was of 74% as opposed to 60% from the one with 30 topics. Moreover, it appears that the students who were given only 6 choices delivered higher-quality essays, possibly meaning that the effect of reduced choice anxiety actually translated into better performance.

Controls for academic performance, isolation of results, time, etc. seem to be in place.

Chocolate Study: 3 scenarios were given to different groups of university students to try chocolates. 1) the first group had no choice, they were assigned a chocolate, 2) the second group had limited choice with 6 alternatives and 3) the third group was given 30 varieties of chocolate. The study surveyed the students on expected satisfaction and difficulty choosing. After tasting the chocolate they reported their level of satisfaction and, finally, they were offered either $5 in cash or a box of a selection of the chocolate. The results were, as my graph said: the highest satisfaction came from the limited choice group, followed by the extended choice and lastly the no choice group. Extensive choice group reported more excitement and frustration with the choice process.

Controls also seem well suited in this study. Although, one thing that jumped out, the no choice group didn’t had the option of declining to take the chocolate.

Issues…

Of course, there are criticisms of this theory. There have been follow up studies and meta analysis made on the subject, that were unable to replicate the effects of the original Jam studies. In an article by Tim Harford on the Financial Times, a meta study was talked about that seems to contradict the idea that Choice Paradox is a generalized phenomenon. A meta study (meta analysis) is a purely statistical (non-experimental) analysis on actual experimental studies that aggregates multiple experiments and tries to derive a generalized conclusion from several independent studies. An analysis of experimental analyses, if you will.

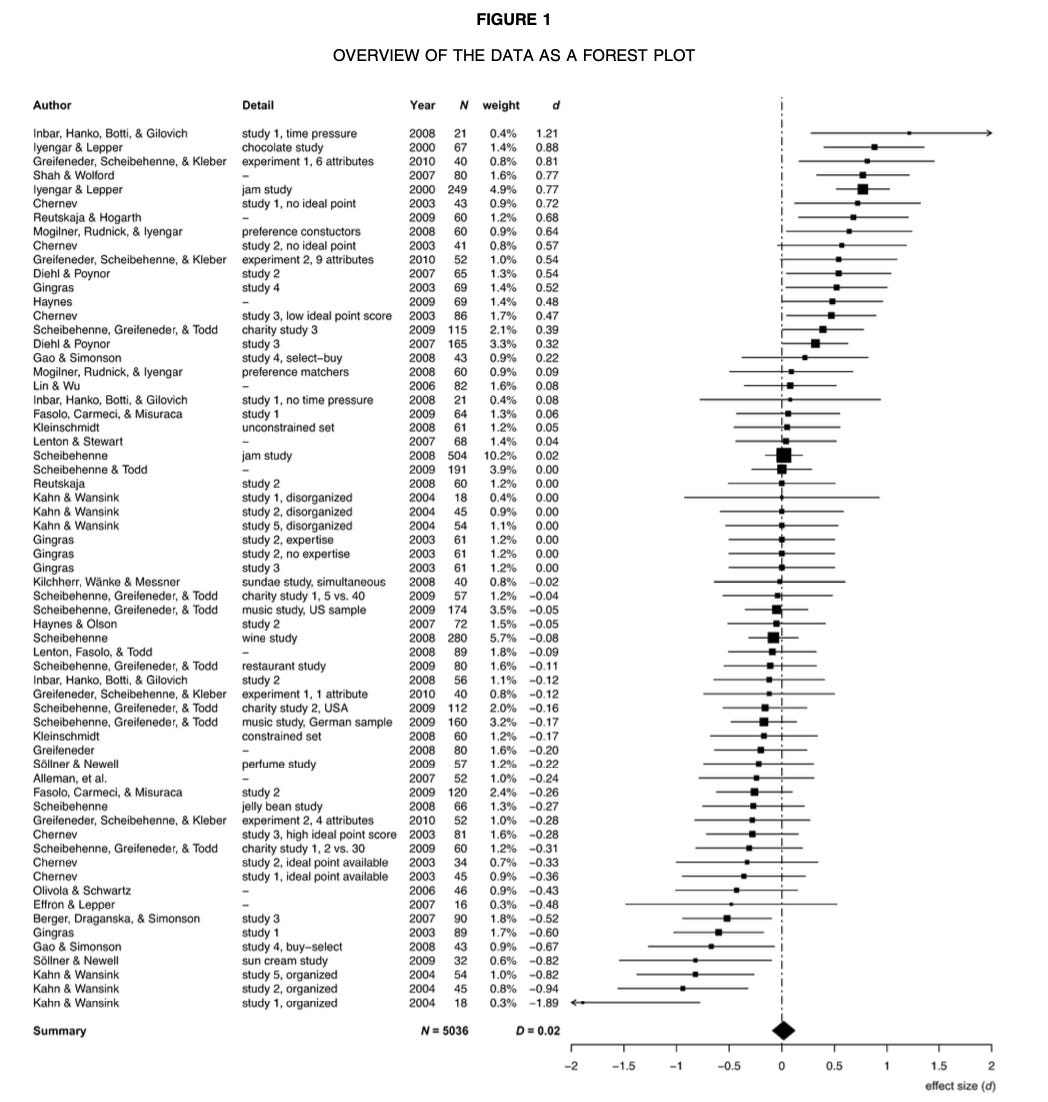

This study by Scheibehenne et. al concludes the following:

In average, adverse effects due to an increase in choice options are not very robust, near zero.

There is high variability of results in between studies

More choice seems better with regard to consumption quantity and if consumers had well-defined prior preferences

More recently 'published papers were less likely to support the choice paradox (the choice overload hypothesis)

In general, the conclusion is that Choice Overload is not a generalized phenomenon, although this, there is evidence to suggest that it can happen given some specific conditions, which is a way of explaining the variability between independent studies. But they don’t concretely point out what these are. Additionally, we can see a chart below. The phenomenon does not appear to show on most studies, only about 38% of the time. (d>0 => Existing choice overload effect, A positive d-value indicates choice overload and a negative sign indicates a more-is-better effect.- page 413 )

The average weighted by sample size is positive, meaning that there is a slight Choice Overload Effect, but it did not appear to be statistically significant. Median and mean are on favor of more-is-better. Most studies showed + choice = better but the cases where it was the opposite the average effect was about 25% stronger on average. The Standard deviation is 11 times the weighted average, meaning there is a whole lot of variability.

The Financial Times article also mentions, as I did in the beginning, that supermarket chains, Starbucks, stores, etc. all have an overabundance of choice and none seem to be on track to simplifying choice, meaning that, at least on the side of actual consumption, more choice actually does appear to increase purchase quantity.

So we are starting to find very nuanced information.

So far

So far we know there are several studies regarding the Choice Paradox or Choice Overload Hypothesis and there is a generalized study that concluded that, on average, the effect is not significant. My big issue with this study is that it assumed that actually making a decision, quantity purchased and choice satisfaction are the same variable. I am much more inclined to accept that extensive choice has negligible or inverse average effect on making a decision or quantity purchased, than the one claimed by the paradox. But, satisfaction with choice can still be up for grabs. Why? well satisfaction is something more complex, that can change way later after purchase and it can retroactively become better or worse, so my gut tells me that optionality could have an impact in after-purchase satisfaction.

Just think about going to a restaurant that has 40 different dishes, for the first time. The menu is overwhelming, especially when the names are not straightforward and after having your meal you might wonder about the 20 or 15 things you would have tried but didn’t, it would make sense to me that satisfaction can be reduced.

More Depth

November 12, 2024 (3rd day). I read a couple of additional articles and studies. I have to add interesting pieces of information:

There is this study about a phonomenon called Single-Option Aversion, this is acclaimed for softly contradicting the choice paradox. In the study subjects were more likely to avoid making a choice of a product if they were presented with one product as opposed to 3 or 4 alternatives. The effect size was 3.5X more likelihood of choice with 3 or 4 alternatives. I don’t think this contradicts the choice paradox, at all. As I, Schwartz and common biblical wisdom has said: everything in moderation is better. The original Choice overload theory does imply that some choice is better than non, but an excess of choice is worse than some. This study did not concerned itself very much with choice satisfaction. To me, this study points to something obvious, humans require frames of reference to understand if something is good, bad or average and some choice can provide this frame of reference. Going back to an earlier graph:

Maximizers vs. Satisficers (Herbert A. Simon): A Maximizer is a person who is searching for the best possible deal (option) a Satisficer is concerned with making a choice that is good enough. Choice Overload is likely to affect Maximizers more than Satisficers. Now, people can and will be both. I’m a Maximizer when choosing a movie to watch but a Satisficer when choosing a meal. I was a Maximizer when choosing what car to purchase, now I just need something that is good enough. Schwartz claims that Maximizers make better quality decisions but they are less satisfied with them than Satisficers

Decoy Effect: presenting a new alternative that is very similar but slightly worse than one that exists makes decision makers much more comfortable and satisfied with choosing the original (better) choice.

Choice Architecture: Framing is a concept that appears in Thinking, Fast and Slow by Kahneman. The basic idea is that the way in which options are presented can widely sway our perception of the actual choices. In this context, the way in which we present options can mitigate or extenuate the effects of the Choice Overload without adding or removing any optionality. Examples are: changing language (ex. changing add product ←→ avoid other product) , Segmentation (ex. breakfast, meals, dinners), Default option (ex. automatically charge tip and give optionality to opt-out), Order of presentation (ex. cheap to expensive or vice versa)

Temporal vs. Long-Term Satisfaction: when talking about choice satisfaction, as mentioned earlier, the topic will be complex because it is a continuously changing variable, especially in the long term. So the studies linked here are not likely to be able to fully follow up on long-term satisfaction, especially regarding short term consumption products

So, after going through this data, I think I understand where the literature is on this topic at this time, relatively decently, still not in an expert way by any stretch.

Results

After a while of making research I came across an article citing the OG, Schwartz, that closed the circle on this research perfectly because he ended up exactly where I wanted to end up, the Meta-Study by Scheibehenne et. al.

In the end, the consensus concludes that Choice Overload Hypothesis exists but is not as generalized a phenomenon as it was once promised to be. It has not been disproven at all; rather, more research is needed to understand under which circumstances it’s more likely to be relevant.

Everything points to the fact that some choice is better than none. There are variables that are likely to explain why sometimes over-abundance of choice is good and sometimes it’s bad. Some examples are given in the PBS article citing Schwartz. But in general, things like: personal preferences about the choice, previous experiences or information, cultural differences, importance of the decision for the decision maker (price, duration, etc.), difficulty of the decision (similarity between options, complexity of the product, etc.) and many other factors are likely to determine the effect of abundance of choice in ease of choosing and satisfaction with choice.

Additionally, my initial estimation on Negative Bias influencing choice satisfaction and procrastination has not been explored, so the conclusion of my informal “eye test meta analysis” are inconclusive. Also, I did not fully got into understanding if less choice => more variability in outcomes for satisfaction, so that is left for some other time.

Conclusion

Apparently, we got to the answer that no one likes, except for economists, we don’t know for sure but it probably depends on the context. In conclusion, how would I explain this in one simple phrase?

Choice Overload in probably real, and sometimes significant under some circumstances. We do not quite know what this circumstances are precisely, so more research is needed to understand the scope, variability and effects of the phenomenon. Some choice is definitely better than none, but the benefits of abundance are not as clear cut. In my estimations, if research on this becomes more sophisticated, we will be able to tell the conditions that contribute to a higher or lower optionality sweet spot. Maybe we even go ahead to find that most of the choice paradox effect was washed away by choice architecture. But, for now, we are not sure either way.

And as promised, the prize, is a picture of my Sister-in-law’s dog, Max: