About 3 years ago I started managing my first fund. It was the weirdest fund, sometimes, when I tell fund managers and people in finance about it, they don’t understand a single word that i’m saying. In retrospect, the Risk Adjusted Return was amazing.

So what is this model that’s so weird?

So, crypto applications (dApps) that run on public blockchains, for the most part, want to be decentralised, they want funding for development and they need some type of governance structure for decision-making.

The initial solution was to create something analogous to an IPO (Initial Public Offering [of stocks]) but with a token that resembled company stocks, these tokens are called Governance Tokens and, generally, people who possess them enjoy the rights to vote on how the dApp is managed and they can, especially lately, accrue direct or indirect benefits when the dApp does well. This model was called an ICO, an Initial Coin Offering, but the ICO model slowly faded since 2019. Why?

The most important reason for the fall of ICOs is regulatory scrutiny, it would move Coins and Tokens closer to a financial “Security” status, which would have led to hostile regulators having jurisdiction over them.

Additionally, founders of projects noticed that initial investors pumped and dumped the token without adding any value to the service

Finally, ICO sales tend to centralize ownership, given a small amount of users have most of the money, and decentralised governance is something that matters to crypto projects

Other models appeared during the 2020s, but the digital asset space hoped to kill 3 birds with one stone by coming up with the concept of an AirDrop. Now, for the purposes of this article, when I talk about dApp stock or shares i’m referring to their governance tokens. Legally they are different because shares imply legal ownership and Governance Tokens just reward voting rights. So the legal structure backing up the benefits from purchasing tokens is really slim compared to shares. But the case of Uniswap potentially distributing dividends and European crypto regulaton helping the legal structure makes them look more and more alike each time.

Crypto Airdrops work the following way: basically, they give away shares of the dApp for free. Why would they do that? well they don’t give it to just anyone.

AirDrops, usually, distribute a predetermined % of their total Tokens (Shares) to the people who are early, avid and noble users of their service. Companies raise money, have initial collaborators and the total number of tokens goes in part to the founders, in part to early investors, some of it to early collaborators (sometimes vested), some of it is AirDropped, and the rest remains on treasury. Proportions and mechanisms vary by project but this is the overall model.

So this way

There is no public sale of shares (VC money in the beginning does not constitute a public/retail sale), they are just gifted => the token is farther apart from a security under the Howey test.

Loyal users of a service tend to see the potential for growth, incentivizing them to hold the token and to actively participate in the governance through voting and making good proposals, making the value add of the dApp better.

Using an app is much cheaper than participating in an ICO, so the ownership is better distributed, allowing more opinions to be taken into consideration on decision making.

Thousands of users want to be early users of your service, because you will gift them shares in return, which makes it more popular, helps fix the bugs and make an overall better product (network effect) that charges fees.

So, basically, my fund hunted AirDrops, I spent investor money being an early user of several apps that had not yet had an airdrop and waited for governance tokens to be allocated to my wallets. All investors knew the risk, technical and otherwise, and the fund was successfully closed way above market yield (vs. S&P500). In the end, the AirDrop era seems to be over, companies never figured out a way to, both, deter people like me that would just dump it and, at the same time, properly reward faithful users, maybe ICO’s will come back with the appropriate regulation, there are some AirDrops now, but nothing compared to the 2021 craze.

But, anyways, one of the hunted applications was Polymarket. And this is how I got introduced into betting markets

Polymarket

Polymarket and Betting/Prediction Markets, in general, allow people to bet on broad events that usually have binary outcomes—either a win or a loss—where they earn or lose money based on accuracy.

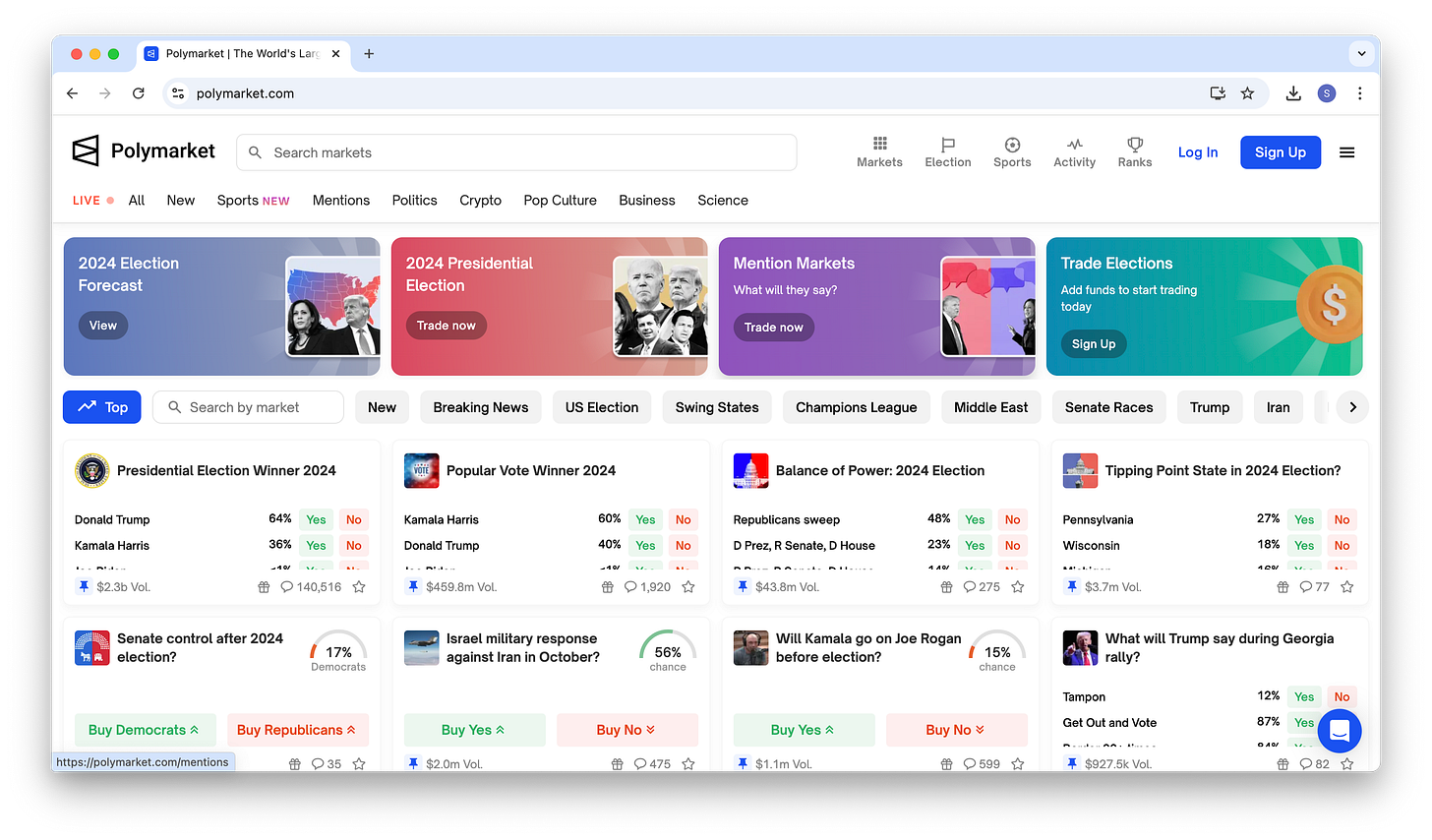

The top market for the last few months in Polymarket has been the presidential race winner, which is a good base example to explain how this works. The election candidates today are The Donald (Donald Trump) and Kamala Harris.

So, Polymarket creates the market, they initially set default odds, and send it to the public. Whilst creating the market, they publicly state a source from where information about the outcome will be drawn and the rules are pre-set. If X thing happens by X date then people who bet on X win, people who bet on anything else lose. The prices of 'yes' or 'no' bets always range between $0 and $1, as they are expected to reflect implied probabilities under the efficient market hypothesis.

When the event happens and the correct option is made evident, those who bet on the correct outcome will be compensated at $1 for each share they have and the losers will receive $0 for each share they have. for example; let’s say I thought the probability of Trump winning was 90% and I bought 10 shares of “TRUMP WINS” at 0.5 USD, meaning I bet 5 USD on trump winning, if Trump wins my 10 shares are worth 1 USD each, meaning i won 5 Dollars, if Trump loses my 10 Shares are worth 0 USD each, meaning I lost 5 Dollars USD.

In the election case, the market will be resolved given announcement of news sources and backed up by the inauguration:

Once the market is created, people start betting on the outcome. Let’s say that I go to the market for Kamala/Trump and see the odds, which currently stand as below:

Notice that they don’t always sum up to 100 cents (1USD), this often relates to market forces, fees, rounding errors, and the fact that there is a non-zero possibility that some of the candidates drops out, pass away, etc. and some other candidate has to take over.

So, at the moment, if you believe Democrats are underrated you will buy a “KAMALA WINS” token at 36.9 Cents, let’s say you buy 1,000 USD of these shares. As said, at the end of the contest (the election) the prices of the tokens set to a binary outcome of $1 or $0 USD/Share let’s set the following:

Trump wins token final price = T

Kamala wins token final price = K

Other democrat wins final price = D and other republican wins final price = R.

MOIC (Multiples on Invested Capital) = Ending Balance / Initial Bet

So the potential scenarios, under the current prices are below

Trump wins election. T = $1; K =D =R = $0

If you buy T at market now $0.632 you will sell at $1 => 1.58X MOIC = 1,580 USD

You choice: Kamala wins election K = $1; T = D =R = $0

If you buy K at market now $0.368 you will, again, sell at $1 => 2.71X MOIC = 2,710 USD

If R or D is the case the MOIC is ($1/$0.001) 1,000X = 1,000,000 USD

There is a final component to this, because the betting market is always open, you can liquidate your positions before the realization event and take a win or cut a loss. So if new information becomes available that might skew your view, you have this flexibility, which makes the market more flexible and more interesting.

Let’s see an example of a how a market got closed:

What is Behind

Those who lose, lose 100% of the capital, and those who win, depending on the type of market, earn money in proportion to the calculated probabilities of winning. More modern types of betting allow for some insurance or “sacrifice” but it’s beyond the point.

Unlike traditional betting—where you wager against the house (casino, sportsbook, etc.)—betting markets require a decentralized counterparty to accept your bet, similar to a derivatives contract but without leverage.

So, for every 1 share I buy at x probability, a counterparty has to cover the opposite side. So let’s say that I buy 1 share at X, and the other party takes my bet at Y, but the probabilities must sum up to 1, meaning Y = 1 - X, meaning that the amount of money in the system is X*1 + (1-X)1 ) = X+1-X = 1, in the end, we will give away 100% of the money to one of the parties. So, the losses of one = winnings of the other. If i bet at 0.3 USD this means that my opposition bets at 0.7, if I win i have to win 0.7 if I lose my opponent needs 0.3.

In traditional vs the house betting, the house unilaterally sets the odds by having actuaries calculate the implied probabilities of different scenarios happening, you can either accept it or not accept it but there is just one counterparty for all bettors that offers the same odds. When having a non-centralized counterparty, different people will accept different odds according to their beliefs and their information. In economics, finance, mathematics, etc. averages have been incredibly important as a way to explaining reality, and averages are an important part of prediction markets.

The argument, for many years now, is that a betting markets are a really precise way to predict events. A betting market, because there is no one centralized counterparty setting odds, can average the opinion of so many people with so many different types and degrees of information, who have financial incentives to be correct, that the information conveyed by the revealed implied probability incorporates, both, all the available information and the confidence each bettor has on its information as a means to arrive to a conclusion. The amount bet could sometimes be held as a proxy for confidence in the result, other times the actual confidence is directly asked. This topic is complicated given bet as a share of disposable income affects volume.

Efficient Markets

The accuracy of prediction markets is often justified through the efficient markets hypotheses, where asset prices always will reflect the correct intrinsic value giving all the available (public) information (different from the perfect information assumption in economics). From this it follows that it is not possible to consistently purchase assets at a lower price than their intrinsic value calculated at the present time, and therefore, because variations are random, it is not possible to consistently beat the market.

Of course, this is not entirely true. All markets have inefficiencies—false reports, conflicts of interest, FOMO, etc.—and betting markets have also demonstrated inaccuracies.

Now, going into the future, when dApps like Polymarket make Prediction Markets more accessible to more people, in general, these theories are going to be put to the test really often, with much more public and transparent information.

Overall, if you want to take a semi-technical, conservative, approach to using this services. You have to have a gauge of how likely you think an event is to happen, if the market is pricing that event at a lower probability than you, your personal expected value from making that bet will be positive. Of course there are other more complicated strategies like betting the underdog on many events in a way one win makes up for all losses, betting arbitrage between platforms, but a simple one-off bet would be the best place to start, as it does not require a lot of mathematical modeling, capital or overall expertise.

Conclusion

Betting markets are particularly interesting because, in my view, probability theory is the most reasonable approach to understanding the world and its intricacies.

In general, the consensus is shifting toward the belief that highly liquid, well-managed, easily accessible, and diverse prediction markets are an accurate measure of event probabilities.

Personally, I don’t like binary betting or casinos, especially casinos, I hate Las Vegas and I hate Mike Tomlin coach of the Pittsburgh Steelers, this has nothing to do with anything, I just wanted to say it jeje.

But, anyways, I do visit Polymarket often as a way to get a sense of likelihood of future events. I do think using betting markets as one of multiple tools, including with more detailed subjective opinions, will be the standard for forecasting.

It will not surprise me, at all, when actuaries, investors, governments, etc. start incorporating Prediction Market odds into their mathematical models. Which could result in an interesting loop because people will use models to forecast the odds and then feed back those odds into the same model. Additionally, it can be used, even by institutional investors, as a hedging mechanism.

In conclusion, going forward, I think all people should stay vigilant of these markets when planning important decisions like voting, credit, mortgages, etc. as one of the tools we have to provide certainty.